This is an English-language version of a chapter from Economia feminista (Feminist Economics), written by Mercedes D’Alessandro. The book provides keys to understanding many longtime debates, and additionally gives a fresh take on central ideas. It aims to be more than just a book about economics from gendered and feminist perspectives: it also uncovers the general issue of inequality from different angles and signals steps towards building solutions.

Chapter II

Desperate Housewives

Why is unpaid housework “women’s work”?

I’ve tried everything women are supposed to do – hobbies, gardening, pickling, canning, being very social with my neighbors, joining committees, running PTA teas. I can do it all, and I like it, but it doesn’t leave you anything to think about- any feeling of who you are. I never had any career ambitions. All I wanted was to get married and have four children. I love the kids and Bob and my home. There’s no problem you can even put a name to. But I’m desperate. I begin to feel I have no personality. I’m a server of food and putter-on of pants and a bed maker, somebody who can be called on when you want something. But who am I? Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique

It was Saturday afternoon and my friend Ivan tweeted, cutely and ironically: “I’m ironing a shirt while listening to Cat Power because I’m very secure in my masculinity”. I retweeted it and added “Here’s a colleague tricked by stereotypes. Is ironing feminine or just listening to Cat Power? Is it wrong not to be masculine?” A deluge of personal stories and reflections began immediately after. Ivan’s simple comment condenses much of what this chapter is about: Why do we assume that housework belongs to women? Or, why do ironing and vacuuming make masculinity vulnerable? And since we are at it: What is mainstream masculinity about?

Worldwide, the time that women and men dedicate to housework is wildly disproportionate: men spend more time at paid work while women are those who do the unpaid work like cleaning, cooking, grocery shopping, and taking care of children and old people. Although this housework is both indispensable and unavoidable for a functioning society, it tends to be less socially and economically valued than paid work. It’s worth thinking about how to respond to the question: how much time per day do you work? In general, the time that we spend going to the supermarket or wiping down furniture isn’t counted as work hours. That housework falls into a kind of limbo for both economic theory and statistics as well as for our own ideas about what is and isn’t work. Nevertheless, its economic value appears (and lightens our wallets) when these jobs are outsourced, whether they be in different kinds of care centers (child care, preschool, nursing homes, summer camp) or a particular service (house cleaning, cooks, nurses, babysitters, or pizza delivery). There we can clearly see that the time spent on these jobs has a price, and freeing oneself of them opens up the possibility of spending that time either working outside the house or having free time.

The asymmetry in the distribution of housework is one of the greatest sources of inequality between men and women. Because it is women who are spending more time on these unpaid tasks, they therefore have less time to study, develop academically, or work outside the home. They also have to accept more flexible jobs (generally more precarious and lower paying) and they end up facing a double shift: they work both in and out of the house. This phenomenon repeats itself in virtually every country and is not often visible because, to a greater or lesser extent, we all assume that these domestic chores are women’s work and that they do it out of love. Gender roles and stereotypes penalize men as well, making it necessary for them to get better jobs with better salaries in order to support and provide for the family, and, in many cases, it takes away the possibility of participating in and enjoying the upbringing of their children.

Time after time

In Argentina, the participation of women in the workplace has grown immensely since the 1950s. What hasn’t changed at the same pace is men’s participation in household chores. Women no longer only hold on to the goal of being a perfect housewife; these days they (also) have to be successful professionals and hard workers. At the same time, men today are much more committed to housework. They cook, they change diapers, they clean, and in general they do things that for former generations would have been unthinkable like setting or clearing the table. Many women proudly proclaim, “My husband and/or children help me out at home,” although sometimes they don’t realize that this phrase propagates the idea that these are chores that are hers and that she is lucky because the men of the house lend a hand.

Even with the loving help that has been growing in recent decades thanks to cultural changes, the participative gap in housework is still high and women are still at the top of the list. In the ranking of “cleaning fanatics” by the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), Turkish women are in first place with an average of 377 minutes per day, followed by Mexicans with 373. Among men, those who contribute the least to taking care of their homes are Korean men, spending only 45 minutes a day with a vacuum in hand.

The countries with the most egalitarian distribution of domestic chores are all nordic (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, and Finland). This isn’t magic. In these countries, society realized that certain elements had to be adjusted. Starting in the 1970s these countries have developed policies geared towards closing the gender gap and making men aware of the importance of their contribution towards household chores. In 1975, more than 25,000 women gathered for a protest in the streets of Reykjavik, nearly 10 percent of Iceland’s population. The protest took the form of a “women’s day off” and it was a strike in which 90 percent of Icelandic women participated by not doing any housework that day. Men had to take charge of the house, the children, and other chores traditionally assigned to women. As a result of this strike, banks, schools, and businesses closed for the day. One year later, the Icelandic Parliament passed a law for equal pay. “What happened that day was the first step for women’s emancipation in Iceland,” says Vigdís Finnbogadóttir, who later became president, and the first female one, of Iceland for more than a decade. “It completely paralysed the country and opened the eyes of many men.” As Lisa Simpson, the little feminist that we have been watching on television for more than 18 years, would say: these girls were simply following the slogan “I’ll iron your sheets when you iron out the inequities in your labor laws.”

If we add up both paid and unpaid work on a global level, the OECD estimates that on average women work 2.6 hours per day more than men. In Argentina, according to the Unpaid Work and Use of Time Survey carried out in 2013, a woman working full time spends more hours doing housework (5.5 hours) than an unemployed man (4.1 hours). In general terms, women do 76 percent of these chores. Additionally, almost nine out of every ten women take part in unpaid work in Argentina, while six out of ten men use part of their time taking care of their children or their home. This implies that four out of every ten men neither cook, nor clean, nor do laundry, nor go food shopping. «In the United States, women spend about four hours a day on unpaid work, compared with about 2.5 hours for men. The difference starts early: American girls ages 10 to 17 spend two more hours than boys on chores each week, and boys are 15 percent more likely to be paid for doing chores, according to a University of Michigan study,» says Claire Cain Miller of the New York Times.

Available statistics show that these lopsided numbers are repeated worldwide. The OECD has a database for some countries in which the various activities that are divvied up between men and women can be seen, such as paid work, housework, child care, sports, sleeping, or watching television. From this it can be derived that in practically all of these economies men are able to enjoy valuable minutes of free time, whereas women spend more time stuck in the routine of household chores.

They say it’s love, we say it’s unwaged work

In 1963 Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, a revolutionary book and one that many people signal as a trigger for a large part of the discussions that were held in the framework of the second wave of feminism in the U.S. In her book, Friedan proposes the idea that American middle-class women are troubled by a negative feeling which they cannot find the words to describe. Most of them have everything they’ve dreamed of: a husband, children, a cute house with a yard, and are economically well-off. Nevertheless, something bothers them deeply, “the problem that has no name”. The desperate housewife breaks up the landscape with an existential question: Who am I? A woman appeared to be defined by her relationship to others as a wife, mother, and housewife and the resolution of her conflicts would have to be resolved within the home.

Many of these desperate housewives had dropped out of school in order to run a household, but once they were inside that refuge they began to feel unsatisfied. Their only compensation was their own femininity. At the same time, this femininity had very particular characteristics: catching a good husband, feeding the children, buying a dishwasher, baking a cake, dressing pretty and being a seductress to keep the flame burning in the relationship. On the opposite sidewalk, says Friedan ironically, are the neurotic women, the ugly ones, the plain Janes and the unhappy women that want to be poets, physicists or presidents. “They learned that truly feminine women do not want careers, higher education, political rights – the independence and the opportunities that the old-fashioned feminists fought for.”

The second wave of feminism raised the flag for, among other things, reproductive rights, sharing child care responsibility, and housework. Its opponents claimed that these were all private issues that should be worked out within the family. This is what led to the slogan “The personal is political.” One of the main schisms that this wave provoked was that of the idealization of the role of housewife. There was, in fact, a channeling towards finding a meaning, figuring out who one was, outside of the home. For these women, this meant trying to recover their individuality as independent human beings. Education and equal working conditions would be the next challenges.

If in these times women were supposed to stay at home and those that worked were stigmatized (it was even said that those that went to college only did so to search for husbands), today, in many cases, the opposite could be said. Women, not only in the United States, moved away from that housewife ideal, some because of personal motivation and others for necessity. Be this as it may, both then and now their housework has been ignored. Our grandmothers spent long hours washing (by hand) the whole family’s clothes. Even though today we have washing machines and other appliances to help out, ironing, cleaning, cooking, bringing children to school, or taking a grandmother to the doctor form part of a complex routine that is repeated daily. All of these chores were, and continue to be, perceived by families, societies, economic theories, and national accounts as acts of love.

The image of a woman limited to the confines of her house helped Silvia Federici, philosopher and marxist activist, to outline the need for women’s struggle and for a salary for housework. Salary, in the society in which we live, signifies being part of a social contract and it is through our salaried work that we gain access to consumer goods which we need: food, clothing, transportation, books, or the movies. One works not necessarily because he or she likes it, but because it is the condition in which we live. The issue of domestic work is that, in addition to not being paid, it has been imposed as a duty upon women, and it has transformed itself into an attribute of the feminine personality: being a good housewife became, at one point, something desirable or characteristic for girls.

According to Federici, women don’t spontaneously decide to be housewives, but rather they go through daily training that prepares them for this role, convincing them that getting married and having children is the most they can aspire to. And this is not something only from the past; many decades later culture still reinforces these roles. Dolls, toy kitchens, tea sets, pink brooms and dustpans, makeup, and bracelet kits are the perfect combination for raising the charming princesses, mothers, and devoted wives of tomorrow. That story is not so far off in a culture of Hollywood movies in which women leave everything for a man’s love. Or even the Latin soap opera variant where the maid is the one who turns into the wife after years of taking care of her beloved employer in silence (additionally becoming upwardly mobile). Full of advertising for excellent cleaning products which, with aloe and lavender, take care of the hands that you will use to caress your loved ones with after cleaning the sediment out of the toilet. A large percentage of our communication systems are still anchored in these stereotypes.

The classic model of a heterosexual couple works in this way as a tacit and reproductive agreement: she cooks, cleans, has kids, is good at sex, and takes care of him. He is the breadwinner and he goes out into the streets everyday to bring home the bacon and the cash to pay the bills with. This is also how he pays for the right to be waited on when he arrives home. Federici, without mincing her words, says that “In the same way as god created Eve to give pleasure to Adam, so did capital create the housewife to service the male worker physically, emotionally and sexually – to raise his children, mend his socks, patch up his ego when it is crushed by the work and the social relations (which are relations of loneliness) that capital has reserved for him.» That which they call love is unwaged work. Dressing up unpaid work as an act of love hides the fact that these chores are, strictly speaking, work. In this way, an activity that is indispensable for a working society is carried out for free in a world where everything that is consumed has a price. From there we get the idea of the movement for a salary for housewives as a way of, initially, making this work visible (my own memory refers to other times when it was said “my grandmother doesn’t work, she’s a housewife,” as if being a housewife wasn’t work in and of itself).

One of the greatest contributions of feminist economics was to a shine light on the work of what was hidden in the market scenario. For Federici it is the zero point for revolutionary practice; it is the core of the discussion; it is where we find the key to transform the productive and reproductive structures of the system. Once we recognize this aspect of social production, issues arise around the valuation of unpaid work and who bears its load. Throughout the history of feminist struggle (and those of public policy regarding gender), different alternatives have been tried out in order to economically value unpaid work. Salaries and pensions for housewives (which put housework on the same level as work done outside the home), parental leaves, universal coverage or state-sponsored care for children, seniors, or people with handicaps, among others. There are many components that economic theory and public statistics do not see and which do not fit into their models, indexes, and policies. Although the surveys used to measure the use of time are quite complicated to carry out and difficult to compare among geographical regions and cultures due to the great variety of facts that we can find expressed within them, they contain valuable information when it comes time to think of solutions and alternatives. The generation of this data helps to close the gap because they allow us to have a map and diagnose the issue. For example, a study that deals with South Africa, Tanzania, South Korea, India, Nicaragua, and Argentina estimates that if a monetary value were to be assigned to the housework that women do, it would represent between 10% and 39% of the GDP in those countries. Additionally, by reducing women’s responsibility of cleaning, shopping, and care-giving, their productivity outside of the home would also increase.

The equation according to which the wife/housewife must sacrifice her career and independence for her family is moving further into the past. Nevertheless, the absence of government policy that provides solutions to the needs of a traditional family and all of the different family configurations (single mothers, divorced parents, single-parent homes) pressures women workers (more than men) to be able to do everything at the same time. Despite the fact that most women are not full time housewives, reality keeps piling those chores on them, to which they also must add their work outside the home.

Behind every great woman there is another woman

New generations have left behind many traditional orders. Nevertheless, taking care of the home and children is still under private control, and, more specifically, that of women. When women are incorporated into the labor market, the cost of having to work both at home and outside of the home becomes more evident. The need for care services which are not always available (at least not for free) begins to appear. Corina Rodriguez Enriquez, a role model in feminist economy, suggests that the one of the most important dimensions of this distribution of household chores is that which is called the care diamond, and in which homes, the market, the government, and community organizations all participate. At home, chores are distributed among the members of the family; the market provides solutions like babysitters or senior living facilities; the state has the possibility of establishing family leave or offering public preschools; community organizations can contribute with cafeterias or sports facilities. There are many options and, of course, they all have a cost.

The main part of the caretaking responsibilities are borne by homes, and it is assumed that the other points of the diamond either collaborate or facilitate the balance between housework and the market. When there aren’t daycares, preschools, or senior living facilities available (or accessible) free of charge, families (above all those with the lowest purchasing power) have to face these chores by themselves, which takes time away from studying, training, accepting paid work, or simply watching something on TV. They have no other option but to cut out the extra activities and appeal to older sisters or aunts for help. High income families, however, have a better possibility of hiring a babysitter or maid and, in this way, they are able to free up time to go to college or the movies. As soon as they can, middle class working women turn to these fairy godmothers who cook, clean, wash, iron, drive, take care of children, seniors, and pets.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), more than 80 percent of all domestic workers in the world are women. At the same time, one in seven working women in Latin America work in the sector in which under-the-table pay is near 80 percent, with incredibly low salaries, extensive work days, and without access to benefits. In Argentina, only 3 percent of the workers in that field are men and domestic work is the main job of wage earning women in the country (nearly 20 percent). The fairy godmothers that “help out” in rich homes, far from having wings and a magic wand, are poor; many have multiple children, and most don’t even have a high school diploma. The maid tends to be a woman who needs to work but does not have the qualifications to get another kind of job. There are also many young women who see this as a possibility to escape the poverty they are accustomed too, although they often end up in the maid’s room in a well-off home, and in most cases are denied basic workers’ rights.

In some countries in which gender politics and feminist discussions are more advanced, doubts have begun to appear around this situation that we’ve been dragging along for centuries. Is it that the richest or most white collar people oppress the poorest and those without education? For some, in this crazy race for success, a group of women suddenly appear who clean their houses and take care of their kids. Moreover, as there is seldom (or never) a man working as a babysitter or scrubbing the floors and washing the dishes, the idea persists that housekeeping and caregiving (of children and seniors) is women’s stuff. Bowman and Cole (2009), from the University of Chicago, propose the idea that the way out from this maze doesn’t have to do with condemning the hiring of women for domestic work, but rather by starting to recognize, value, and professionalize these chores with the end goal of improving the way in which we all perceive them and also the quality with which they are carried out. But the value our society puts on things is monetary. That’s why if we want cleaning women or babysitters to work under better conditions they need to have higher salaries. And therein lies the problem for professional middle class women: in countries with high rates of social inequality and high levels of unemployment it is easier to find poor women with little education willing to work in a home for a lesser amount of money. Revaluing domestic work implies that it would become more expensive. For families of the middle class it’s better for them if they can pay low salaries, because by any other way they wouldn’t be able to hire anyone, and without help they wouldn’t be able to work outside the home.

What’s more, according to the regional director of the ILO (Latin America and the Caribbean) Jose Manuel Salazar, is that there is also “a situation of complex discrimination, with historical roots in our societies in systems of servitude and with attitudes that contribute to making women’s work invisible, many of those women being indigenous, descendants of Africans, and immigrants.” In many cases these workers are exploited physically, mentally, and sexually. At a global level, Latin Americans make up 37 percent of the domestic workers in the world, in second place behind Asia. “This work, insufficiently regulated and poorly paid, continues to be the main supplier of caregiving, due to the lack of universal public policies in most of the countries in the region,” explains Maria Jose Chamorro, a gender specialist at the ILO.

Therefore, because “the personal is political,” the state has such an important role in providing care systems. The government could help to make it so that the mechanism of inequality doesn’t grow larger between the richest women who utilize the services that the poorest women provide. The professionalization of caregivers also improves the quality of employment for these workers that in any other way are pretty economically punishing. Another necessary step is the denaturalization of these tasks as being thought of “women’s tasks”. As Obama said, «We need to keep changing the attitude that congratulates men for changing a diaper, stigmatizes full-time dads, penalizes working moms.»

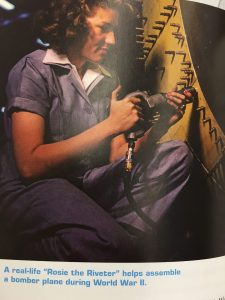

We Can Do It

One of the most iconic posters of feminism is that of a woman with a red bandana on her head, a shirt with the sleeves rolled up showing her muscles, and a slogan that says “We can do it”. The image is from World War II, when many American women took the places in factories and shops that were left by men who had been called to the front. A higher level of women’s participation in the workforce isn’t necessarily something positive in and of itself; oftentimes this growth has been a product of wars, economic crises, and poverty. At the same time, the labor market is no paradise: women earn less than men everywhere in the world; they face higher rates of unemployment and precariousness in work; maternity penalizes their salaries and opportunities and they have difficulty gaining access to certain activities or climbing up the hierarchical ladder. Female professionals are blocked from moving upwards by hurdles, and for the poorest it is hard to even go to school. Neither rich nor poor women are saved from the gender gap.

Even when the circumstances are far from ideal, there are still major elements for the advancement of women towards the world of paid work. The massive access of education for women was crucial not only to help improve their labor conditions but also for their personal development or simply to feel better about themselves, as Betty Friedan observes. Women today have more freedoms, options, and rights than those who were alive only 50 years ago and although that isn’t reflected in access to better job positions or the political system, women have an enormous potential which we are going to see explode at any moment. Education is the main factor of progress and democratization, and it is a path towards equalling out opportunities.

No less important in this story is the role of scientific and technological advances with regards to reducing the work hours necessary to do housework. The introduction of the washing machine in the lives of housewives is comparable to the revolution generated by the Internet. The impact that freed up time has, whether it be via fairy godmothers or appliances (or both of them together) is measurable: according to figures from the OECD for a handful of countries, when women are able to reduce their household routine from 5 to 3 hours per day, the rate of their participation in the workforce rises 20 percent.

Birth-control pills profoundly changed the possibilities for better family planning, and they are one of the factors that everyone who studies the issue signals as decisive in order for women to be incorporated in the workforce. Cell phones and computers, as were mentioned earlier, allow access to information, the ability to look for work, online education, as well as making working from home easier.

It is not about rejecting housewives, but rather the contrary: understanding that without the work that women do today (and which could be redistributed), society would lose its cornerstone. Unpaid work needs to be recognized for what it is: an indispensable job for all social life and the foundation on which daily economic activity is hoisted. If we were able to reorganize this valuable work in a more equitable way between men and women and, furthermore, among homes, the government, and caregiving institutions, there would be more opportunities for a more equal and happier society. We would also be transforming a historical relationship, because achieving equality at this zero point implies a complete reconfiguration of the world in which we live. That is where we need more guys like Ivan, who can relax while ironing in the afternoon without feeling weird about it. The idea of a Wonder Woman who can be successful in every area of her life is a nice way to look at a problem that, more than anything, needs to be solved.

Three poems for women (Susan Griffin)

1.

This is a poem for a woman doing dishes.

This is a poem for a woman doing dishes.

It must be repeated.

It must be repeated,

again and again,

again and again,

because the woman doing dishes

because the woman doing dishes

has trouble hearing

has trouble hearing.

2.

And this is another poem for a woman

cleaning the floor

who cannot hear at all.

Let us have a moment of silence

for a woman who cleans the floor.

3.

And here is one more poem

for the woman at home

with children.

You never see her at night.

Stare at an empty place and imagine her there,

the woman with children

because she cannot be here to speak

for herself,

and listen

to what you think

she might say.

Translated by Jonah Schwartz